Stratis Morfogen Has Big Plans

Posted by estiator at 13 December, at 07 : 19 AM Print

FEATURE

With ambitious new restaurants, a cookbook, and a frozen-food line, the entrepreneur is making the pandemic a time of opportunity.

By Michael Kaminer

Stratis Morfogen does not think small. His Brooklyn Chop House became a glitterati destination for its splurgy Asian-steakhouse fusion menu and 5,000-square-foot room in New York’s Financial District. His Pappas restaurant, set to open this March, will bring a lavish, 500-seat Greek steakhouse to Manhattan’s West Village. His robot-driven Brooklyn Dumpling Shop, a quick-service concept slated to open in the East Village this month, promises nothing less than a revolution in self-serve dining [see “Back to the Future,” on the last page of this article]. And it’s all happening against the backdrop of a relentless pandemic, an economic downturn, and brutal headwinds for restaurants. For Morfogen, though, there’s never been a better time to dream big.

“People are scared to make moves like this, and it is scary,” he tells Estiator. “But I’m cut from a cloth that when there’s a fire, I run into it, not away. Great wealth and success comes from down markets. There’s been no better time in decades to take action.”

The luxurious Pappas restaurant might represent the most audacious bet of Morfogen’s three-decade run as an entrepreneur. Inspired by a downtown Manhattan seafood-andchops joint his grandfather and three great-uncles ran from 1910 until 1970, the new Pappas will occupy 14,000 square feet spread over two floors on Manhattan’s MacDougal Street. “One of the goals of my career has been to bring the original Pappas name to the Morfogen family,” he says.

The concept will bring something new to the Village, emphasizing steaks along with seafood offerings that traditionally characterize Greek dining. “[Legendary meat purveyor] Pat LaFrieda is helping me architect a butcher area married to a fish display. We’ll be the only Greek restaurant to offer 10- and 35-day dry aged prime meats. Greek restaurants do great with fish, but they don’t usually pick prime, dry-aged meat,” Morfogen says. All meat, fish, casseroles, and even pita will get cooked in custom-built, wood-burning ovens. “This is a quality play,” Morfogen says. “We’re going oldschool. It’s a change from the traditional Greek restaurant.”

The fact that Morfogen is investing in a fine-dining destination at a chilling time for restaurants has only motivated the restaurateur. His bet may turn out to be a canny one. The New York Post reported Morfogen “will pay the greater of $700,000 base rent or eight percent of the gross. Even if it works out to as much as $1 million a year, it’s a remarkably reasonable cost for so large a venue on a heavily trafficked block. The deal includes a generous tenant-improvement allowance.”

I’M ALL FOR EDUCATION AND THEORY, BUT IF YOU DON’T HAVE STREET SMARTS AND PRACTICALITY, IT’S USELESS

As Morfogen told the newspaper, “These are the kinds of opportunities we’re not going to see again in our lifetimes.” Even the broker who engineered the deal for the space was astonished. “When someone told me about it, I thought, ‘What’s he smoking?’ Most places there are so small, I thought he meant 1,400 square feet, not 14,000,” James Famularo told the Post.

That is exactly the point, Morfogen tells Estiator. “Look, I have a friend who bought a building in Tribeca. His closing date was September 12, 2001. He just sold the building for $100 million dollars. Even after September 11, we knew things weren’t going to stay like that forever. There are huge opportunities out there right now.”

Morfogen’s strong stomach might come from his Greek-immigrant roots and century-long family history in restaurants. While his grandfather had emigrated in the early 20th century, Morfogen’s father, John, arrived from Anavrati, Sparta, in 1947; his mother’s family came to the U.S. from Gythio, Sparta, 10 years later. Morfogen grew up on the floor of his father’s seafood restaurants around New York City. “I was born in Queens and grew up in Garden City, Long Island. My dad had 14 restaurants, and he never even had a weekend off. I worked in every capacity, from cleaning toilets all the way up. My dad used to say that you can’t teach someone to clean a toilet out of a book. You can only learn by doing it.”

As a serial risk-taker who proudly touts his high school education, Morfogen also believes that only experience can teach entrepreneurship.

“I’ve been an entrepreneur since I was 19 years old,” he says. “I now teach courses about entrepreneurship. Colleges and universities don’t understand what kids need. It’s not physics and calculus. That won’t help you in the world of business. Schools fail when it comes to teaching entrepreneurship.”

Instead, he says, “your post-graduate education should be practicality. On-the-job experience is your master’s degree. I’m all for education and theory, but if you don’t have street smarts and practicality, it’s useless.” Even Morfogen’s own attention deficit disorder—which inhibited him academically, because “people didn’t know what ADHD was”—has become “a huge asset,” he says. “I’ve been on my own for 30 years, and I’m 52 now,” says Morfogen, who lives in Manhattan with wife Filipa Fino and daughters Beatriz, Isabel, and Natalie.

His ventures veer all over the culinary and geographic maps; while not all of them have succeeded, as Morfogen himself admits, all of them have drawn crowds, made headlines, and enjoyed an aura of glamour.

His first business, launched with a $25,000 loan from his father, was the concessions and restaurants at a Long Island amusement park; he grew revenue by a factor of seven before selling it.

With his father, Morfogen opened Hilltop Diner in Queens, bringing in a well-known chef named Danielle Moran to generate some heat. It became a smash; that success enabled him to open Gotham Diner on Manhattan’s Upper East Side in 1993 and cross over into nightlife by launching Rouge nightclub in 1994.

After a stint transforming New York’s iconic Fulton Fish Market into a digital commerce brand, Morfogen met celebrity chef Philippe Chow; the pair launched a midtown restaurant named for the chef, which quickly became the nation’s highest-grossing restaurant per square foot. Morfogen split from Chow after legal issues arose with the chef’s former employer.

In 2016—during a self-imposed break from the restaurant business— music-industry executive Robert Cummins approached Morfogen about operating a restaurant in a space Cummins owned in Manhattan’s Financial District. Though Morfogen hadn’t considered opening a new eatery, the offer sparked his imagination.

“My wife and I used to eat at [famed Brooklyn steakhouse] Peter Luger. We’d enjoy these beautiful steaks, but everything else was weak—creamed spinach, baked potatoes, parsley, iceberg lettuce,” he says. “With my background in Chinese restaurants, I dreamed up a new concept: LSD, or lobster, steak, duck. Why couldn’t you have sea bass and black-bean sauce along with steak? Why not Peking duck?”

Brooklyn Chop House was the result, and the restaurant has been a destination since opening day. “There’s not a place on Earth that can put all the things on the table the way we do—a Pat LaFrieda 48-ounce steak, two pounds of salt-and-pepper lobsters, Peking duck carved tableside,” he says. “I realized the next generation of diners is not embracing the baked potato.”

What they are embracing is Morfogen’s visions of dining, whether it’s a line of frozen entrées launched in partnership with Patti LaBelle—yes, that Patti LaBelle—or a new book on dumplings set for release this month [see “The Right Stuff,” on the previous page].

“We’ve all experienced such pain and hurt the past few months, but there are huge opportunities out there,” he says. “This is the moment in real estate, in small business, and in being an entrepreneur.”

THE RIGHT STUFF

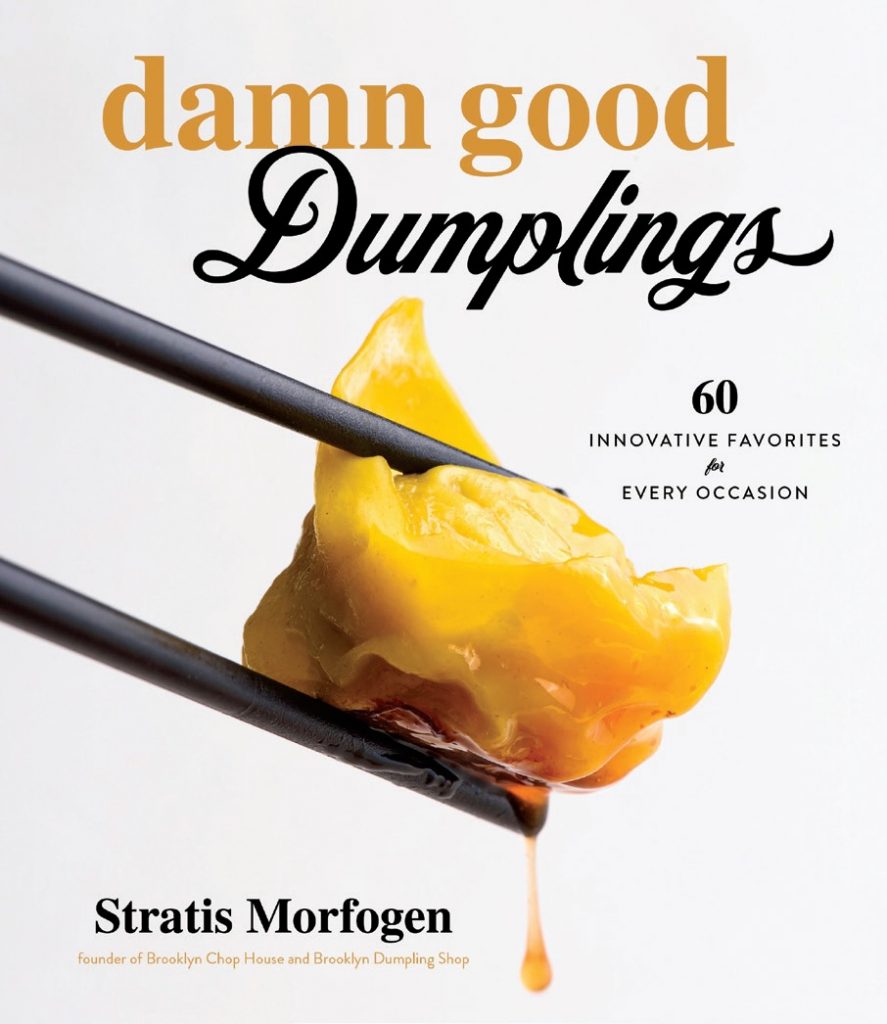

Morfogen’s new book, Damn Good Dumplings, offers up 60 wildly creative recipes.

The title of Stratis Morfogen’s new book is as blunt and straightforward as it author. And like Morfogen himself, Damn Good Dumplings (Page Street Publishing) gets wildly creative. If you think a dumpling just means kreplach or wonton, you’ll find 60 surprises in this book, from cheesesteak, corned beef, and pastrami dumplings to grilled ginger chicken, “funky chunky vegetable,” and short-rib stacked.

Not coincidentally, Morfogen’s quick-service, no-contact dumpling concept is due to launch this month; Brooklyn Dumpling Shop will feature several recipes from the book, all prepared by robots. At his Brooklyn Chop House in Manhattan, dumplings have been unlikely hits, including lamb “gyro,” lobster “spring roll,” and crispy steamed pork varieties.

“The results are in the numbers, and Brooklyn Chop House has doubled all projections because of the dumplings. When Page Street Publishing’s executives got wind of it, they insisted I write a book on it,” Morfogen tells Estiator. “I came up with 60 versions of my ‘sandwich dumplings,’ including everything from turkey club to peanut butter and jelly dumplings. I strongly believe in ‘who-said-you-can’t?’ thinking when it comes to creating and cooking. Food is something that brings all cultures together, and that’s why I wrote Damn Good Dumplings.”

Judging from the book’s celebrity endorsements, he’s onto something. Star chefs like Eric Ripert, Daniel Boulud, and Todd English all blurb the book, along with entertainer Patti LaBelle, Morfogen’s partner in a line of frozen foods set to launch at Walmart.

But for Morfogen, there’s also an emotional component to the book:

“Watching the faces of my children as I’ve used the dumpling to introduce new foods to them when they were very young. But the real aha moment was when I took traditional sandwiches like pastrami, bacon cheeseburger, lamb gyro, and the Philly cheesesteak and made them into dumplings and watching our guests smile from ear to ear,” he says.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

Brooklyn Dumpling Shop reinvents the automat as contact-free dining.

Talk about back to the future. While it relies on robots and technology to create a no-contact experience, Stratis Morfogen’s Brooklyn Dumpling Shop has roots in a classic eating establishment: the automat, where customers once served themselves from vending machines in cafeteria-like settings.

“When Horn and Hardart created the automat in 1902, it became a thriving business—through the Spanish flu, and into the ’40s and ’50s, until fast food killed it in the ’70s,” said Morfogen, who is launching the quick-service franchise concept in Manhattan this month. “It’s probably the most effective, cost-efficient way to distribute food to consumers, but technology ultimately failed it.” Morfogen expects more than 400 locations to be contracted over the next three years; five will stay company-owned.

Part of Brooklyn Dumpling Shop’s mission will be to reclaim that illustrious legacy, with a very 21st-century twist. With hands-free self-ordering kiosks and an app-based ordering and fulfillment system, the brand will become the first to enable a Zero Human Interaction experience in quick-service restaurants, Morfogen claims.

“It’s 100 percent robotic, with robotic arms coming from the ceiling to do the work,” he said. “Before, you’d need a kitchen crew of seven to do something like this. Now you need about two. Like the automat, you don’t need cashiers or a counterperson.”

In suburban locations, the ordering process will be controlled by phone, with drivethrough footprints of just around 700 square feet. “You’ll place your order from your driver’s seat, get a bar code, get a green light when your order’s ready, pull up to the building, scan your bar code, open a locker door, and take your food,” Morfogen explains.

The technology, all of it proprietary, also means payroll can shrink to about 15 percent from the typical 28 percent at quick-service franchise concepts, Morfogen says. “The goal is actually to get payroll below 15 percent,” he says. “If I can do that, we’re going to have a lot of success.” Franchise development company Fransmart is representing Brooklyn Dumpling Shop globally.